How we learned to teach ‘small children’

The philosophical roots of education for the under-sevens

The fifth in a series of highlights from my Learning Through the Ages blog, originally published on historyofeducation.net.

Seven up

Before the Industrial Revolution, grammar schools, public schools and other places of formal education were mostly attended by children over the age of seven, a milestone which had been established by the philosophers of Ancient Greece, who invested that number with great significance. Hippocrates (c460-c370 BC), for example, divided human life into eight periods of seven years each, with the first stage being 'small child', and a similar scheme was adopted by Aristotle (384-322 BC). As the Greek education system evolved, 'small children' were brought up informally at home by their mothers or handed over for moral instruction to the ‘pedagogue’, a slave too old or infirm for other types of work.

In contrast with modern times, the informal play that occupied most of children's time was not invested with any educational significance, it was merely ‘childishness’. Aristotle and his teacher Plato were highly unusual in thinking that children’s games could be directed to educational purposes, but their ideas on this front would not be absorbed into educational practice until the modern era (1).

Mothers were the de facto educators of pre-school age children in Britain all the way until the Industrial Revolution which took women out of the home in large numbers to work in the new factories. Many relied upon small private ‘dame schools’ to look after their youngest children while they were at work. These were mostly run by uneducated women who, like the ancient pedagogues, were infirm or otherwise unable to work. Some lucky pupils may have been taught the alphabet, but in educational terms most dame ‘schools’ were misnamed, amounting to little more than glorified childcare (2).

However, the Enlightenment that had given birth to the Industrial Revolution also generated new thinking about child development, which would have a profound effect on education for the under-sevens. Several thinkers in particular set the context for the practical experiments that followed.

Following a child's interests

The English philosopher John Locke (1632-1704) criticised grammar schools for paying scant regard to a child’s natural interests or to the knowledge and skills they would need as adults. His An Essay Concerning Human Understanding (1689) and Some Thoughts Concerning Education (1693) sketched out a tentative theory of child development: a child’s mind at birth was a ‘tabular rasa’ (blank slate) and all knowledge and understanding was arrived at through experience. The gradual cultivation of rationality was a prerequisite for adult participation in society. Locke also recognised the role of motivation in learning, and argued for a reorientation of education away from teaching predetermined knowledge and towards the interests and curiosity of children, a view that will resonate with many teachers today (3).

The idea of following a child’s interests would be explored in much greater detail and rigour over half a century later by the Swiss philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712-1778), who believed that curiosity and imagination are innate to all children but are drummed out of them by formal education. His Emile, or On Education (1762) was an imagined account of the raising of a young boy – the titular Emile – by encouraging him to pursue his own interests. At each stage Emile’s encounters with people and his experiences with nature were carefully contrived by his tutor to encourage his understanding and curiosity about the world to grow. Think an 18th century version of The Truman Show (4).

Rousseau himself was hardly a model parent, having abandoned his own children, and Emile may have been intended as a metaphor for society rather than a literal manual for child raising. Its one-tutor-to-one-pupil model - an extreme form of what we'd now call personalised learning - was certainly not easily applicable in mass education, but nevertheless the book caught the imagination of the middle classes across Europe and prompted a number of attempts to emulate its approach and, later, to develop the idea for use with groups of children.

Harmony with nature

Swiss educator Johann Heinrich Pestalozzi (1746-1827) attempted to put the methods of Emile into practice using his own son as a guinea pig, which led to disappointment when said son did not learn to read or write or demonstrate any particular talents. This prompted Pestalozzi to develop a more practical version of Rousseau’s ideas. Picking up themes from both Locke and Rousseau, he believed that education should harmonise with a child’s nature and devised a system of teaching in line with a child’s capacity at the various stages of development.

Pestalozzi was against rote learning and cramming of facts, preferring to set children questions and problems to solve in order to stimulate their thought processes and curiosity. (This was not a novel concept - the 8th Century educator Alcuin of York had set his students mathematical puzzles with the same aim in mind - but in the era we are discussing it was far from common practice). Pestalozzi's concept of ‘teaching by things’ was given practical form in ‘object lessons’ during which children would discover as much as possible about the objects they were presented with using their senses before any descriptions or explanations were provided by the teacher (2).

Irish inventor Richard Edgeworth (1744-1817) was another parent who tried to emulate Emile, by bringing up his first son as a ‘child of nature’ and leaving him ‘as much as possible to the education of nature and of accident’. In doing so he either misunderstood or chose to ignore the manipulative aspects of Rousseau’s scheme, which involved constant oversight, planning and intervention. At any rate, the result of his experiment, he later acknowledged, was an obstreperous and overly self-willed child (5). Chastened by the experience, Edgeworth and his daughter Maria rejected theory in favour of empirical research, and this would lead to the first ever systematic study of child behaviour, which they wrote up as Practical Education (1798). This argued that younger children should learn predominantly through play and experimentation rather than instruction.

Infant schools and socialism

Many of these ideas fed either directly or indirectly into the first infant school in Britain, set up in New Lanark, Scotland in 1816 by Robert Owen (1771-1858), factory owner and founder of British Socialism. Owen was one of many who visited Pestalozzi’s school in Yverdun and was impressed by the methods used and the attempts to match the form of education to children's developmental stages.

Like Locke and Rousseau, he believed that education was the route to a better society. For him, the first step on the road to socialism – a political philosophy of cooperation rather than competition - was to teach children to cooperate, in the hope they would maintain that habit in their adult lives. Kindness was encouraged, beatings and threats by teachers were disallowed, and classrooms were decorated with displays, maps, and paintings of animals and natural objects. Activities included singing, dancing, marching to music, fife-playing and geography, with three hours a day spent outdoors in an open playground. Books were notable by their absence.

2-4 year olds and 4-6 year olds were taught separately, before moving into the main schoolroom at age seven where they would stay until they started work in the mill at age ten.

Other infant schools sprang up in England and the master of one of these, Samuel Wilderspin, would become the greatest promoter of the schools, touring the country, giving lectures and helping start local schools. He had considerable insight into young children’s thinking and behaviour but, in contrast to Owen, was more interested in solving existing social problems than bringing about radical social change. His On The Importance of Educating the Infant Children of the Poor (1823) adapted the instructional tradition of the traditional schools rather than Owen’s developmental approach.

A typical infant school on Wilderspin’s model consisted of a large hall with blackboards on the walls for children to write and draw on. Subjects taught included drawing, music, physical exercises, sewing, knitting, gardening and early steps towards reading and writing, as well as the aforementioned ‘object lessons’. One radical departure from traditional day schooling was his suggestion that pupils spend ‘at least half the school time’ in a playground containing revolving swings, ropes for jumping, wooden building blocks, flower beds and trees.

Wilderspin’s model was considered to be more practical than Owen’s, and it was his that prevailed. But even its more idealistic elements fell by the wayside in practice, and the half day in the playground was often abandoned. Nevertheless, the infant schools he set up or inspired became an appealing option for working class parents, not least because they charged only one to two pence per week, half that of dame schools (2). By the time of Wilderspin’s retirement in 1847, there were over 2,000 infant schools in England (6).

A new demand for teacher training

At this time, most infant teachers had, unsurprisingly, not been trained on the needs of early childhood. Addressing that was a priority for David Stow (1793-1864), who had founded the Glasgow Infant School in 1826, inspired by the work of Wilderspin and Pestalozzi. Stow believed that education had been overly concerned with the intellect and should instead aspire to train the 'whole man', another view that is widely held today (albeit expressed in the gender-neutral terms of 'the whole person'). To that end, in 1837 he established the Normal Seminary – the first teacher training institution in Britain – which would end up sending trainers around the world (7).

In the same year Elizabeth Mayo’s book Lessons on Objects: As Given to Children Between the Ages of Six and Eight in a Pestalozzian School, At Cheam, Surrey was published. It became a success and would help explain the ideas of infant education to teachers. She and her brother Charles, who had worked at Pestalozzi’s school in Yverdun, were among the founders of the Home and Colonial Infant School Society, which opened a training college in London, offering six-month courses for infant teachers. By 1843, it was training 100 teachers a year (2).

Nursery schools

Demand for infant education continued to grow and would lead in turn to a demand for nursery schools for even younger children. A number of factors were involved. More children were surviving babyhood. Child labour was gradually restricted by successive Factory Acts, and increasing mechanisation meant there were fewer suitable jobs for children anyway. Workers’ wages were rising and working mothers were now able to pay to send their children to the comparatively clean and safe environment of an infant school.

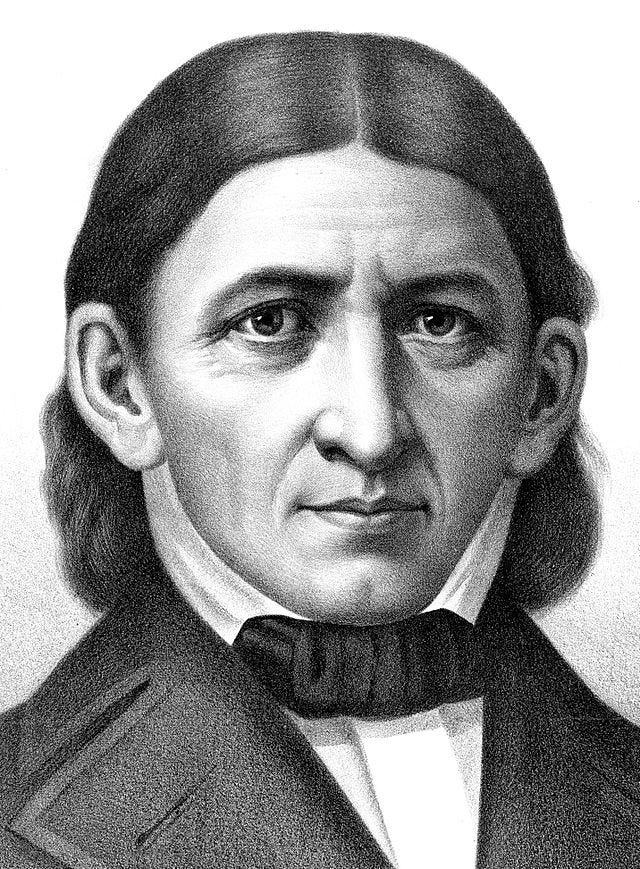

However, many working parents could only let their six- and seven-year olds attend school if they took their younger siblings with them, which created practical challenges for teachers. The existing schools tried to accommodate the additional children as best they could, but dedicated nurseries began to appear from the 1850s, inspired by German pedagogue Friedrich Froebel (1782-1852), who set up the first kindergarten (‘children’s garden’) at Keilhau in 1837.

Froebel had worked for Pestalozzi at Yverdun and was impressed by his approach, although he thought a more systematic educational theory was required. He believed that education should not begin until the child felt a need to learn and, like Richard and Maria Edgeworth, he attached a lot of importance to play, creating graduated exercises based on children’s games. He also developed activities which aimed to develop children’s motor dexterity and designed apparatus to help them learn the elementary laws of physics. To this end he gave pupils six ‘gifts’ – wooden balls, cylinders and cubes which were intended to be playthings, as well as symbols of the child’s growing consciousness of the universe.

However, the conservative regime in Prussia were disturbed by the professional opportunities that kindergartens gave many women and banned them in 1851. This led some of Froebel’s followers to move to England and the first kindergarten in England was opened in Bloomsbury, for children of German liberals escaping from Prussia. It soon becoming a hub of training and promotion for the kindergartens that opened up in its wake over the next two decades in London, Manchester and Leeds (2).

What happened next?

No doubt you'll have recognised concepts above that have become common features of Primary school and nursery life, such as the outdoor playgrounds of Owen and Wilderspin. The proliferation and development of formal education for under-sevens during the late 19th and 20th centuries is outside the scope of this article, but if your interest has been piqued, I highly recommend Nanette Whitbread's fascinating The Evolution of the Nursery-Infant School (1975), which follows the story through to the comprehensive school era.

Today, the ideas of Locke, Rousseau, Pestalozzi, the Edgeworths and Froebel still resonate widely and underpin the progressive education movement that has influenced our modern education system in so many ways. Though some of their theories were misplaced, their insights into child development and behaviour undoubtedly contributed to making schools more humane and compassionate places and laid the ground for the modern field of educational psychology.

We have come a long way from treating the first seven years of life as mere 'childishness', although we still have a lot to learn about how children's minds work. Yet, we may not be comfortable with all the consequences of treating young children's behaviour as an object of scientific enquiry. Many educators are now convinced that the first years of a person's life determine what follows. This has raised the stakes for parents and teachers, who are expected to micro-manage every stage of a child's development, causing much unnecessary anxiety, stress and disappointment for those involved. Some educators now look wistfully abroad to countries such as Finland where school still begins at seven. I'm not convinced that's the answer, but we could certainly do with relaxing a little and re-embracing the ineffable aspects of 'childishness'.

We should also recognise what is unique and distinctive about the later stages of life. In recent decades, the boundaries between different stages of childhood and adulthood have become increasingly blurred, with, I would argue, a negative impact on education. Ideas about the role of play in young children's learning have been inappropriately applied to much older children and even to adults. It is unwise to infantilise people who are no longer infants. Yes, we should treat small children as children, but a truly progressive education system also treats teenagers as young adults and adults as grown ups.

Bibliography

A History of Education in Antiquity by H.I. Marrou (Sheed and Ward, Inc, 1956)

The Evolution of the Nursery-Infant School: A History of Infant and Nursery Education in Britain, 1800-1970 by Nanette Whitbread (Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1975), chapters 1-3

Some Thoughts Concerning Education by John Locke (1693). Available on Google Books.

Emile, or On Education by Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1762)

Memoirs of Richard Lovell Edgeworth, Esq. by R.L. and M. Edgeworth (1821). Available on Google Books.

Samuel Wilderspin and the Early Infant Schools by W.P. McCann (British Journal of Educational Studies, vol. 14, no. 2, pp. 188-204, 1966).

History of Education in Great Britain by S.J. Curtis (University Tutorial Press Ltd, 1963), chapter 11