Frances Mary Buss, the first ‘Head Mistress’

A tribute to the pioneering 19th century teacher and campaigner for women’s education

The second in a series of highlights from my Learning Through the Ages blog (historyofeducation.net).

A woman’s place

From the 6th century, when grammar schools were established in order to prepare young men to join the clergy, right up to the onset of the Industrial Revolution, boys were the main beneficiaries of formal education. History of Education in Great Britain by S.J. Curtis tells us that any girls who were lucky enough to attend schools were usually taught domestic skills such as spinning, knitting, sewing and strawplaiting. A women’s place was in the home and their education was shaped accordingly. (1)

Early feminists such as Mary Astell (1666-1731) and Mary Wollstonecraft (1759-1797) argued that women were just as rational as men and that they desperately needed a broad education if they were ever to break free from their social confines. However, even as the Enlightenment was in full flow, British society was not ready for these radical and progressive thoughts. ‘So far as cleverness, learning and knowledge are conducive to women’s moral excellence, they are desirable, and no farther,’ wrote Mrs Sarah Ellis in Daughters of England (1845), as just one example of the prevailing sentiment. (2) Higher education was not yet an option for women, who were also barred from attending meetings of many of the learned societies in which intellectual life thrived. (3)

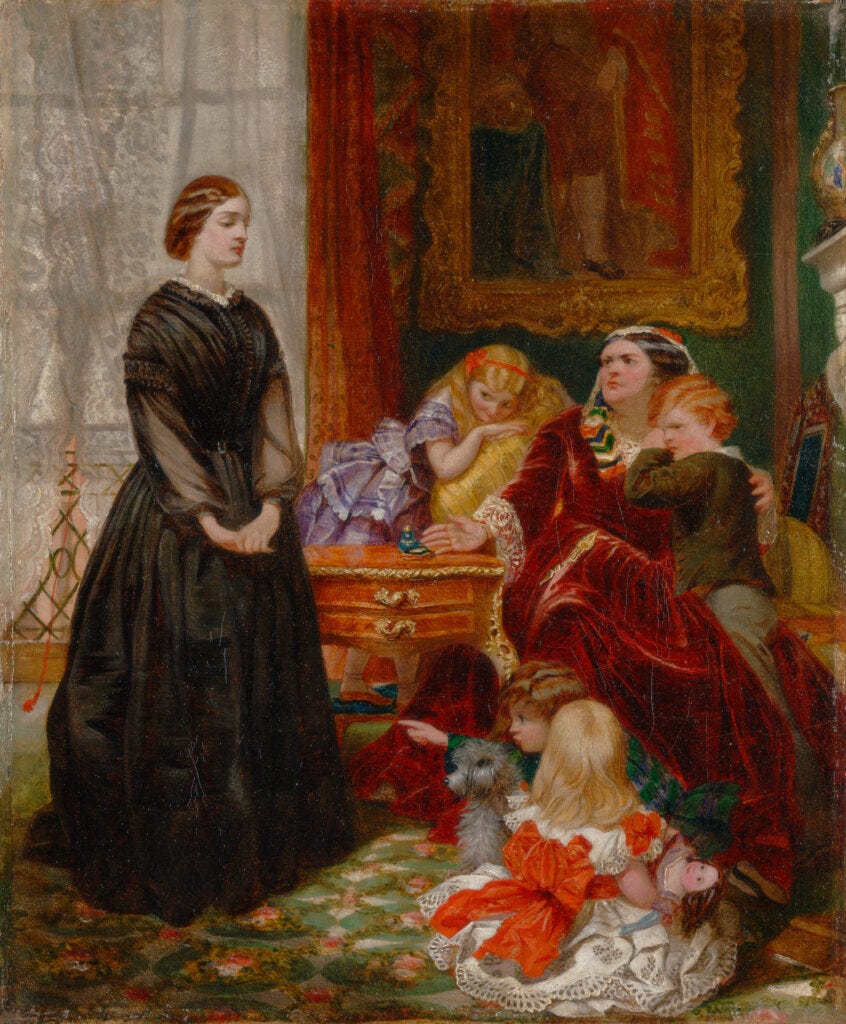

In Nigel Watson’s book And Their Works Do Follow Them, we discover that the young ladies of the upper and middle classes were expected to learn only what would bolster a future husband’s home and social life: ‘Gentle trills on the piano, a little conversational French, a charming song or two, sketches of picturesque ruins and some delicate tapestry work’. (4) Their daughters were effectively brought up to be ‘ornaments in society’, as 19th century feminist Frances Power Cobbe put it. (3) To provide this very limited form of education, upper-class families would either hire live-in governesses or send their daughters to one of the handful of expensive boarding schools for girls that had sprung up since the 1600s. Middle-class girls were typically taught domestic skills at home by their mothers.

Perhaps surprisingly, girls from poorer families were the first to benefit from the social and educational changes brought about by the Industrial Revolution. As work for many men and women shifted from the home to factories, their daughters as well as their sons had to be looked after during the day and were sent to the charity schools that had been established during the 18th and early 19th century. There they received a basic moral education, alongside a smattering of the three Rs. Some of these girls went on to become maids in middle-class homes, where they often found they knew more than the young ladies they were serving. For their employers, this was an embarrassing state of affairs that could not be allowed to continue. (4)

A new demand for educated women

The situation provoked a clamour from middle-class families for governesses to teach their young daughters. Being a governess happened to be one of the few respectable professional careers for a woman at this time. In Victorian Britain, there were many more women than men (half a million more, according to the 1851 census of England and Wales) and the financial pressures this created within families gradually made it acceptable for ‘superfluous’ (unmarried) women to earn their own living. The role of governess had the advantage of being conducted within the employer’s home and away from public view and disapproval. (3)

When the Governesses’ Benevolent Society was formed in 1843 to support the growing profession, it found that most of the women who came to it lacked the experience and knowledge required to teach. Many couldn’t even spell. So the Society established Queen’s College in Harley Street as a training college for young women over the age of 12. (It was named, of course, for Victoria, who encouraged the initiative and provided for a number of scholarships).

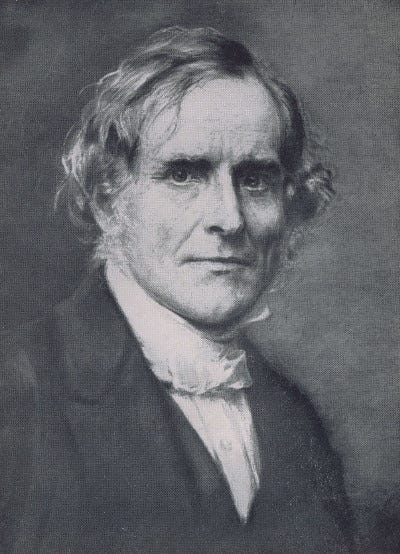

The College launched in 1848. In his book Queen’s College: 150 Years and a New Century, historian Malcolm Billings tells us that the college’s founder, Frederick Denison Maurice, had been brought up in a Dissenting family with a strong tradition of education. Maurice was a believer in knowledge for its own sake and a supporter of education for women and working men, and would become a key figure in the Christian socialism movement. (3)

Inspired by the post-1830s revival in public schools of liberal education, which was open-ended rather than designed to train people for specific roles, Maurice organised a curriculum that was radically broad for the time: English Literature and Grammar, Drawing, Mechanics, Method in Teaching, Geology and Arithmetic. The latter was thought to be particularly ‘dangerous’ by the College’s critics – on the principle that young women could not be expected to fully understand the subject and ‘a little knowledge is a dangerous thing’ – but Maurice defended it for providing women with a ‘truer glimpse’ of God’s universe, which could not possibly do them any harm.

Maurice was a professor at King’s College and persuaded many of his colleagues to give evening lectures at Queen’s for no payment. One of the earliest attendees of these lectures was Frances Mary Buss.

From teacher to proprietor

Buss was born on 16th August 1827 and grew up in Mornington Crescent in Camden, North London. Her father was a reasonably successful artist and engraver but his unpredictable earnings forced the rest of the family to find work. Frances Mary earned money teaching from the age of 14 and would go on to help her mother set up a private prep school in Kentish Town. (4) Her love of learning was encouraged by her father, whose library of books she enthusiastically consumed, and from an early age she would question the different treatment of the sexes: ‘Why are women so little thought of? I want girls educated to match their brothers.’ (5)

Buss happened to be acquainted with a patron of Queen’s College, the vicar David Laing, having attended his church in nearby Haverstock Hill. He was a cultured and liberal man who encouraged her to take evening classes at the college. For four nights or more a week over the next two years she made the long and tiring journey by foot to Harley Street and back, motivated by the opportunity to learn from the eminent scholars Maurice had recruited. She later said of the experience:

“Queen’s College opened new life to me, I mean intellectually. To come into contact with the minds of such men was indeed delightful, and was a new experience to me and to most women who were fortunate enough to become students.” (5)

Buss went on to gain certificates in French, German and Geography, while continuing to teach during the day. Her studies gave her the confidence to pursue her ideas about women’s education, and upon leaving the college she established the North London Collegiate School for Ladies (later renamed ‘…for Girls’) in the Buss family home at 46 Camden Street. On 4th April 1850 the school admitted its first pupils and Buss became a head teacher at age 23.

It was Buss who coined the term ‘Head Mistress’. She was opposed to the titles typically used by women running schools – such as Principal and Superintendant – as she thought they conveyed a lower status. She was determined to have equality with men. If male heads were ‘Head Masters’ than she was going to be a ‘Head Mistress’.

NLCS was a private school but it was forced to charge moderate fees, since boys were the first priority for spending in most families. Money would always be a struggle for the school, and Buss was known to forego her own salary when times got tough. The Brewers’ and Clothworkers’ Companies provided valuable support in the form of loans and money for an assembly hall, but those were exceptions. A public appeal for cash to fund new buildings raised only a few hundred pounds, in contrast to the £60,000 donated for a new boys’ school in the area.

Nevertheless, Buss worked hard to promote the school and, within eighteen months of its opening, the initial 38 girls had grown to 115, hailing from a variety of middle class backgrounds. The school outgrew its building and eventually moved to Sandall Road in Kentish Town where a blue plaque dedicated to Buss can be seen today. In 1871, she would found a second school for younger children from poorer backgrounds, the Camden School for Girls, with over 700 girls attending the two schools. (4)

One of the first pupils to attend both schools, Sara Burstall, would go on to write a glowing biography of her Head Mistress. Buss had a wonderful empathy for children and did her best to make all the girls, especially boarders, feel welcome, as she knew from her own experience the value of a warm and loving childhood. As the school grew, she inevitably became more remote, but maintained her connection with the pupils by addressing the whole school once a week. She spoke of the importance of accuracy, thoroughness, honesty and truth and, although these moral lessons were not always appreciated at the time, Burstall says they made a lasting impression on many of the girls and were ‘the best lessons they had in their school’.

The school’s ethos was imbued with the democratic principle that was fermenting in society at the time. As Burstall put it, Buss aspired to ‘a republic of knowledge’ available to all sexes and races, which recognised ‘no class distinction, no narrow sectarianism’ and involved ‘preparation for life, not the drawing room’. (5) She did not try to create star pupils but instead aimed to achieve a good average attainment in each class. Visitors remarked upon the lack of class rivalry among children and parents. The school’s tolerant outlook was extended to Catholic pupils, in an era when rivalry between the denominations was still strong. It was the first Anglican school to respect Jewish observance and, remarkably for the time, included a young black Jamaican girl amongst its pupils.

Buss’s progressive ambitions applied to her staff as well as her pupils. She worked hard to find talented and capable women to teach at the school and encouraged them to participate in meetings on policy and to write for periodicals. When the school became a trust, Buss ensured there were women among its governors and trustees, which provided them with valuable experience of public life. (4)

A liberal educator

In public, Buss pragmatically downplayed the liberal elements of the school’s curriculum in favour of ‘the usual Accomplishments’, not wishing to put off the wealthy and conservative local gentlemen who might support the school or send their daughters to it. The school’s stated aim was to educate future mothers so that they might ‘diffuse amongst their children the truths and duties of religion’ and ‘impart to them a portion of that mass of information placed by modern education within the reach of all.’

But the school motto – ‘We work in hope’ – hinted, tentatively, at a greater ambition and reflected the humanist idea at the heart of liberal education: a conviction that those you teach will put their new knowledge to good use. (4)

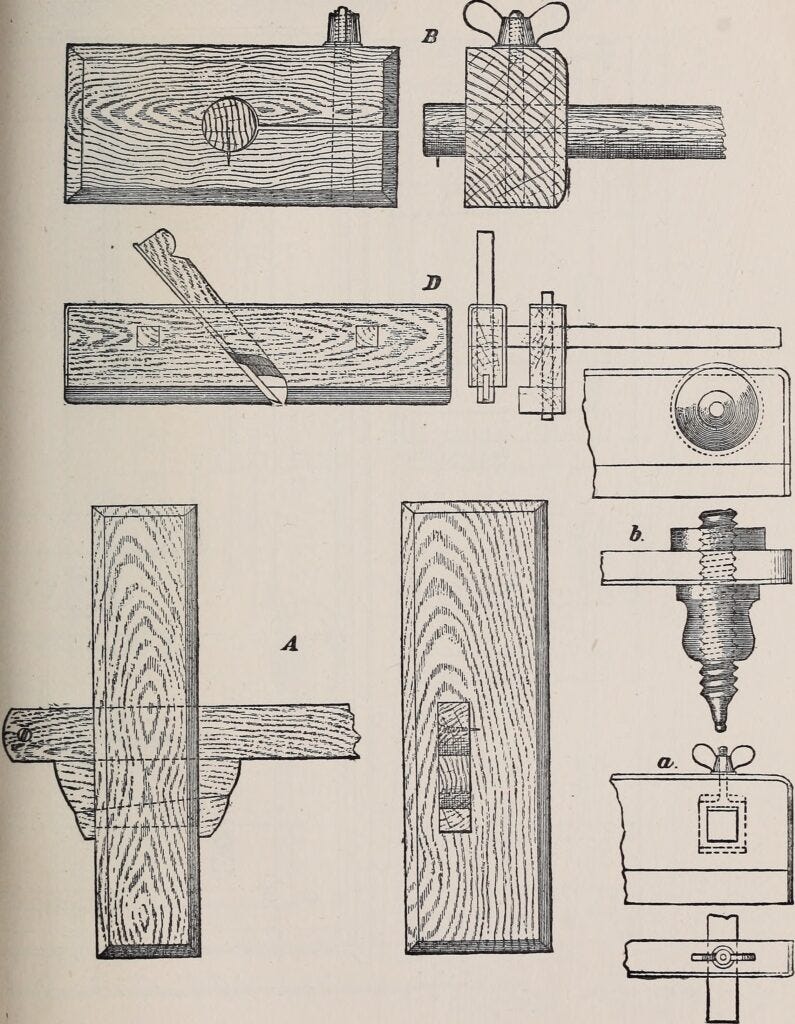

Buss knew that a broad liberal education was the key which could open doors for her girls, although figuring out what that education looked like in practice involved continuous experimentation and refinement. Buss was obsessive about detail and her students complained that she taught Shakespeare pedantically. But she was open to new methods, such as ‘Slöjd’, a Swedish approach to teaching elementary woodwork, the Ablett system of drawing, which encouraged drawing from memory and imagination, and conversational techniques for teaching foreign languages. (5)

The school struggled with its music teaching, but gained a reputation for excellence in Science, and Buss added elementary physics, practical chemistry and botany to the timetable. The curriculum would be praised for its breadth by a London University inspection team. (4)

Incredibly to modern minds, during the Victorian era the very process of education was widely thought to be too stressful for girls, and there were even concerns it could endanger their ability to bear children. Women were also thought to be too emotional to apply themselves seriously to learning or to benefit properly from it. This view received dubious backing from the science of the day, which found that women’s brains were several ounces lighter than those of boys. An 1887 lecture given by eminent scientist George J. Romanes concluded that ‘…on merely anatomical grounds we should be prepared to expect a marked inferiority of intellectual power in the former.’ (3)

Despite her forward-looking views, Buss was not completely immune to contemporary ideas about women’s capabilities, as can be seen in her justification for teaching girls Maths and Latin: ‘…intellectual training effects greater moral improvement in women than it does in men, because a woman’s faults of character, on an average, turn more on irrationality and lack of nerve control.’ (5)

Buss was well aware of what was at stake and discouraged any behaviour that would prevent her pupils being taken seriously. If a girl pretended to faint, as was the fashion at the time, Buss would throw water over her and dare her to do it again. (4)

She also went out of her way to preempt public concerns about the impact of education on her pupils’ health, organising a series of lectures on the human body to teach the girls how to stay fit and healthy and instituting mid-morning breaks for buns and milk. (5) In the school’s open air swimming sessions at St Pancras Baths, the girls were restricted to 15 mins in the water to avoid catching a chill, and if a girl was soaked during a rainy journey to the school, their clothes would be dried on one of the school’s open fires.

Gymnastics were conducted under the supervision of a female doctor but organised games were still considered to be too taxing for girls, so the first NLCS athletic sports day in 1890 was kept low key, in an attempt to attract as little public attention as possible. ‘Only’ six NLCS pupils died between 1880 and 1896, which, given the state of public health at the time, could be counted as vindication of the school’s approach.

The biggest contributor to changing attitudes, however, was the school’s academic success. In 1863 women’s rights campaigner Emily Davies persuaded Cambridge University to allow girls to sit its Senior Local Examinations, which had been established a decade earlier to provide an external standard for grammar school boys to strive towards. (5) Buss supplied many of the candidates for the experiment and the results persuaded Cambridge to carry out a further three-year trial, with girls sitting the same subjects, syllabus and examinations as boys, a situation which became permanent in 1867.

This experience convinced Buss of the value of external examinations, as they enabled her to demonstrate to the world that, whatever the scientific research might say, girls were just as intellectually capable as boys. All the same, the first results came as a shock to her, since almost half her girls failed at arithmetic. Buss learned a valuable lesson – that she had underestimated both the lack of knowledge of the girls on entering the school and the inadequacy of some of its teaching. This provoked an urgent focus on arithmetic, and by 1866 every NLCS candidate passed the exam.

It would be another decade before universities allowed women to take degrees, the first of which was the newest, the University of London. Colleges for girls were established at Oxford and Cambridge, but as they did not share Buss’s view that boys and girls should receive the same education, she refused to send them her students, directing the girls instead to Girton College, which had been set up independently in Cambridge by Emily Davies and would not be granted full college status until 1948.

In 1880 Clara Collet became the first Old North Londoner to receive a BA, at the University of London. A year later, the deputy head of the school, Sophie Bryant, and a former pupil, Florence Eves, were the first women to be awarded BScs (both achieving first class honours). (4)

Legacy

The scope of Buss’s activities are remarkable and extended well beyond the two schools. Although not a naturally confident public speaker, she gave an impressive performance at the 1865 Schools Inquiry Commission which assessed standards in schools. She served on councils of new colleges for girls and fought for governing boards to include women, a principle which would be given official backing after her death, in the Education Act of 1902. (5) She formed the Association of Head Mistresses (now the Girls’ Schools Association) and, along with her deputy Sophie Bryant, the Cambridge Training College for Women Teachers. She also helped establish the Teachers’ Guild, which aimed to promote the welfare and independence of all teachers. (4) Buss was a founder member of the Kensington Society discussion group which evolved into the London National Society for Women’s Suffrage. (7)

The curriculum at NLCS continued to develop under her leadership, encompassing subjects as diverse as elementary physics, practical chemistry, the philosophy of business, bookkeeping, cookery, preparation for the Civil Service, and dress-making ‘on scientific principles’.

While the majority of alumni of the school became teachers, missionaries or, following the lead of Florence Nightingale, nurses, several were pioneers in professions which had been previously been off-limits to women. Lillian Murray become the first qualified female dentist in 1895. Agnes Robertson became a Fellow of the Royal Society. The influential social worker Theodora Morton and birth control campaigner Marie Stopes were both former pupils of the school. Others forged careers in horticulture, pharmacy, photography, interior decorating and furnishing.

Poor health eventually forced Buss to scale back her considerable workload, but she never fully retired. She died age 67 on Xmas Eve 1894, two months after her final visit to the schools. 2,000 people came to her funeral.

Buss must have derived considerable satisfaction from the progress made by her contemporaries. Fellow Queen’s College pupils Dorothea Beale and Elizabeth Day became the first heads of Cheltenham Ladies’ College and Manchester High School for Girls respectively. NLCS supporter Maria Grey became a founder of the Girls’ Public Day Schools Company, which counted Buss amongst its shareholders. By the end of the century there were 80 endowed girls schools in England and Wales, with curricula inspired to varying degrees by NLCS. (4)

The school moved to premises in Edgware in 1940 and continues to thrive today. Be sure to read Nigel Watson’s excellent book And Their Works Do Follow Them to find out about the work of Buss’s successors right up to the end of the twentieth century.

Conclusion

Buss never married. She sacrificed her personal life in the cause of education for women. Most of her evenings were spent attending social events in the hope of meeting potential supporters: ‘I can do more good for the school often in an evening like this than by a whole day at my desk: one can see people and talk to them’.

Her efforts undoubtedly aged her. But as Sara Burstall would comment, ‘what did that matter when the end was achieved?’ (5) Buss proved something remarkable for the time (and which is still contested by some today) – that girls are just as rational, and just as capable of being educated, as boys. This helped pave the way for many of the advances towards equality made in Britain over the last century and half.

She did this in the face of considerable philosophical and practical resistance from society, and she had the intellectual bravery to ignore the authorities of the day who said ‘it can’t be done’. Her story is a valuable reminder that we should not let narrow scientific views of human nature restrict our ambitions.

Again and again, she refused to give up when she encountered obstacles. Burstall remarked that, in Buss’s weekly moral addresses to the school, she would tell the girls ‘if there were a hedge in front, and we could not get through it, we must get under it, or over it, or round it. We must get somehow to the other side’. Get under it, over it or round it – as we face the problems of the 21st century, that’s an attitude we could all do with emulating.

Bibliography

History of Education in Great Britain by S.J. Curtis (University Tutorial Press Ltd, 1963)

The Daughters of England, their Position in Society, Character and Responsibilities by Mrs. Sarah Ellis (1843). Text available on Google Books.

Queen’s College: 150 Years and a New Century by Malcolm Billings (James & James Ltd, 2000). Available via Amazon.

And Their Works Do Follow Them: The Story of North London Collegiate School 1850-2000 by Nigel Watson (James & James Ltd, 2000). Available via Amazon.

Frances Mary Buss: An Educational Pioneer by Sara Burstall (Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge, 1938)

Queen’s College, Harley Street entry at British History Online

Spartacus Educational entry on Frances Buss